|

1 Imperial Cancer Research Fund Department of Medical

Oncology. St. Bartholomew's Hospital. and Lahoratory of Membrane

immunology. Lincoln's inn Fields. London

2 Department of Haematology. St. Bartholomew's Hospital. London

Introduction

The introduction of three and four drug combination chemotherapy

into the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in adults

has resulted in complete remission being achieved in approximately

70% of cases (Willemze. Hartgrink-Groeneveld, 1975; Jacquillat and

Weil, 1973; Gee and Haghbin. 1976; Muriel and Pavlovsky, 1974; Atkinson

and Wells. 1974; Einhorn and Meyer, 1975; Rodriguez and Hart, 1973;

Whitecar and Bodey. 1972; Spiers and Roberts. 1975). In spite of

the use of early central nervous system prophylaxis and continuous

maintenance chemotherapy. however. the duration of complete remission

remains considerably shorter than in childhood ALL. It is well documented

that certain presentation features influence the prognosis in childhood

(Henderson, 1969; Simone and Holland. 1972). We have. therefore.

analysed the data from 42 adults in whom complete remission was

achieved to determine which presentation features influence the

prognosis in adults.

Materials and Methods

A. Patients

Between November 1972 and December 1976. /62 consecutive previously

untreated adults with ALL were treated with combination chemotherapy

at St. Bartholomew's Hospital. All patients received adriamycin,

vincristine. prednisolone and L-asparaginase, as previously reported

(Lister. Whitehouse. 1978). and complete remission was achieved

in 43 (69%). One patient returned to India without maintenance therapy

and subsequently relapsed. The remaining 42 cases form the basis

of this analysis. All recieved early central nervous system therapy

and continuous maintenance chemotherapy until relapse or for three

years. whichever was shorter.

B. Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of ALL was based upon conventional morphological criteria

(Bennett and Catovsky. 1976) for May-Grunwald-Giemsa stained bone

marrow smears. which showed at least 30% infiltration by agranular,

Sudan Black negative blast cells. The periodic-acid-Schiff (PAS)

stain was performed in all cases and considered positive if more

than 5% of the blasts exhibited block or coarse granular activity.

Cases with an occasional fine granular or negative reaction were

also negative for napthol-As-Acetate esterase activity. Cytogenetic

analysis showed that all patients were negative for the Philadelphia

chromosome.

C. Treatment Programme

The treatment programme included three main elements: the induction

and consolidation of remission, treatment of central nervous system

(CNS) or CNS prophylaxis. and maintenance treatment.

I. Induction and Consolidation of Remission At the start of the

study we planned to give doxorubicin (adriamycin) and vincristine

every week tfor a minimum of four courses regardless of the peripheral

blood count. But the incidence of pancytopenia after the 2nd injection

was so high that the schedule was modified and the 2nd course of

doxorubicin and vincristine was given at least l4 days after the

first. The interval between the later courses of doxorubicin and

vincristine depended on the bone marrow findings.

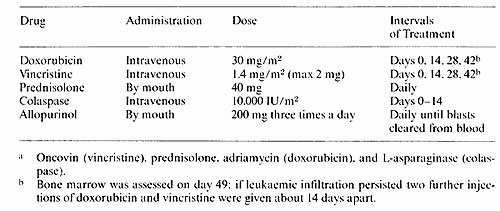

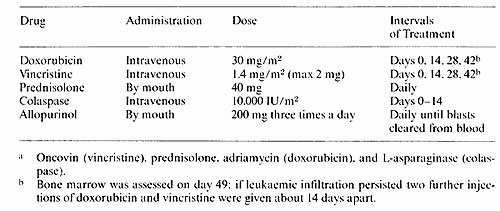

Table I. Treatment given for inducing and consolidation

remission (OPAL a)

2. CNS Prophylaxis and Treatment

In the early part of the study lumbar puncture for CSF cytology

was not performed until clinical and haematological remission had

been achieved . Patients with no evidence of infiltration then proceeded

to CNS prophylaxis. This consisted of cranial irradiation (2400

rads) given in 15 fractions over three weeks with concomitant intrathecal

methotrexate 12,5 mg twice weekIv for five doses during the same

period. Analysis of the CSF findings in the first 28 patients who

achieved complete remission indicated a high incidence of asymptomatic

leukemia disease (Lister and Whitehouse, 1977). The first injection

of intrathecal methotrexate was therefore introduced during the

induction of remission, when the platelet count reached 50 X 10

high 9 /1 in the absence of circulating blast cells. The total number

of doses of methotrexate was also increased to seven. Patients with

proven CNS disease who were in clinical and haematological remission

received more intensive radiotherapy and intrathecal chemotherapy.

Cranio-spinal irradiation (2400 rads) was given in 20 fractions

together with 5 doses of intrathecal methotrexa te 12,5 mg followed

by five doses of intrathecal cytarabine 50 mg given over four weeks.

3. Maintenance Treatment

This consisted of oral 6-mercaptopurine 75 mg daily, starting when

complete remission had been achieved and always after allopurinol

had been stopped. Once CNS therapy had finished oral cyclophosphamide

300 mg weekly and oral methotrexate 30 mg weekly were started together.

The doses of all the drugs were adjusted to maintain the total white

cell count at 3 X 109/1 and treatment was continued for three years

and then stopped.

D. Cell Surface Marker Studies

The panel of membrane markers used included spontaneous sheep red

blood cell rosette formation (for T cells), reactivity with anti-human

immunoglobulin (for E cells) and with anti-ALL serum (for "common

ALL" cells). Ficol- Triosil density gradient separation of peripheral

blood or bone marrow samples was used to separate blasts and mononuclear

cells. The sheep red blood cell rosette (E-rosette) tests was performed

by addition of a suspension of 1 X 10 high 6 test cells in 50 µl

of medium with 50µl of foetal calf serum (absorbed with sheep

red blood cells) to lOO µl of a 2% suspension of sheep red

blood cells which were neuraminidase treated (15 U/ml at 37°C for

30 minutes). The cells were centrifuged at 400 g for 5 minutes and

left undisturbed at room temperature for 1 hour before gentle resuspension

and counting in an haemocytometer. The anti-immunoglobulin serum

was a fluoresceinated F(ab1 )2 preparation of sheep antibody to

human IgG (courtesy of Dr. I. Chantler, Wellcome Research ). It

was used in a direct immunofluorescence technique by incubating

1 X 10 high 6 test cells in 50 µl of medium containing 0,02%

sodium azide. with the anti-immunoglobulin at a 1 in 10 final dilution

for 30 minutes at 4 Celsisus. washing cells 3 times and counting

in suspension on a slide with a Zeiss Standard 16 phase contrast

microscope with epifluorescence and narrow band FITC filters. The

anti-ALL serum has been previously described in detail (Brown and

Capellaro. 1975). It was raised in rabbits against non- T, non-B

ALL cells coated with antilymphocyte serum. After extensive absorption

with normal haemopoietic cells. lymphocytes and acute myeloid leukemia

cells, it was functionally specific for the majority of cases of

non- T, non-E ALL and some cases of chronic myeloid leukemia in

"lymphoid" blast crisis (Roberts and Greaves, 1978). This antiserum

was used in an indirect immunofluorescence technique by incubation

for 30 minutes at 4°C with 1 X 106 viable cells in suspension, washing

cells twice and then incubation for 30 minutes at 4°C with a goat

anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antiserum which was fluorescein labelled.

The cells were then washed 2 times before counting in suspension

as above.

E Statistical Analysis

Remission duration curves and graphic presentations were developed

by standard life table formulae (Armitage 1971) and statistical

significance was determined by the Log Rank analysis method (Peto

and Pike, 1977). The significance of clinicopathological correlations

was determined by the Mann Whitney U test.

Results

A. Overall Duration of Remission

The data from 42 patients are evaluable. Twenty two have relapsed.

One elected to stop maintenance after 8 months and relapsed shortly

thereafter. He has been analysed as not having relapsed, but as

being in continuous complete remission for 8 months. One patient

died at home during an influenza epidemic whilst in complete remission.

The remainder continue in complete remission between 7 and 64 months.

The median duration of complete remission was 21 months. Seven patients

have already been in continuous remission more than 3 years.

B. Influence of Presentation Features on Remission Duration

I. Age The age of the patients at presentation did not influence

the duration of remission. The number of older patients is small,

so statistical analysis would be unwise. However, only 2 patients

out of9 over the age of40 have relapsed. both at 4 months: the remainder

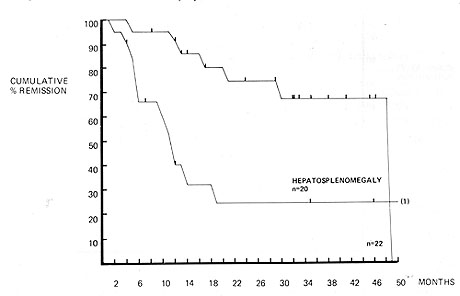

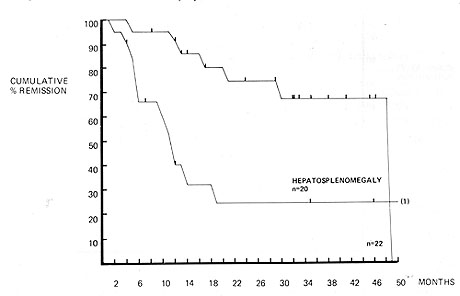

continue in remission between 4 and 46 months. 2. Bulk of Disease

at presentation I. Hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 1) Both the liver and

spleen were clinically enlarged in 20 patients. Only 6 of these

patients remained in complete remission. compared with 15 out of

22 patients in whom there was not hepatosplenomegaly. The duration

of complete remission was significantly shorter for patients with

hepatosplenomegaly (p = < .001 ). II. Blast count at presentation

All 4 patients in whom the presentation blast cell count was greater

than 100 X 10 high 9/1 had relapsed by six months. However. comparison

of the duration of remission for patients with blast cell counts

above and below 10 X 10 high 9/1 reveals no statistically significant

difference. 3. Cytochemistry The PAS reaction was positive in 20

cases and negative in 22. There was no

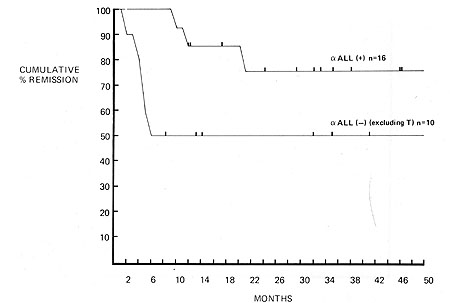

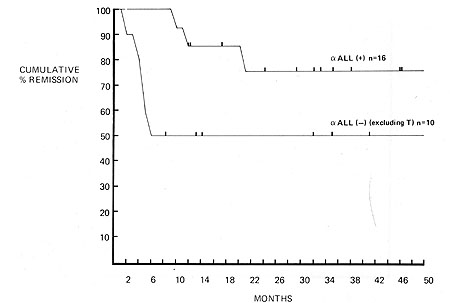

Fig. I. Duration of complete remission in acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Influence of reactivity with anti-ALL serum

difference in the duration of complete remission between the 2

groups. Ten out of 20 patients in whom the reaction was positive

have relapsed, the remainder being in complete remission between

12 and 64 months. Eleven out of 22 patients in whom it was negative

have relapsed, the remainder being in complete remission 2 and 25

months. 4. Cell Surface Marker Studies These were performed in only

29 cases in whom complete remission was achieved. The remaining

13 cases were not studied because they were treated before the techniques

necessary were in routine use in our laboratory and not enough viable

cells were stored to allow frozen samples to be tested. Thus the

duration of follow-up of these cases is shorter than that of the

whole study and the median duration of complete remission has not

yet been reached. Complete remission was achieved in only 3 out

of 5 cases of Thy-ALL. Two have relapsed at 5 and 10 months, and

the third continues in complete remission at 35 months. The blasts

from 16 of the remaining cases of unclassified or null ALL reacted

positively with the anti-ALL serum. The duration of remission was

significantly longer than that of the 10 cases of which did not

react with the antiserum. Only 3 out of 16 anti-ALL positive common

ALL cases have relapsed. The remainder continues between 7 and 46

months. Six out of the 10 anti-ALL. non- T, non-E cases have relapsed

and only 4 remained in remission between 8 and 41 months (Fig. 2

).

Fig.2. Duration of complete remission in acute

lymphoblastic leukemia. Influence of hepatosplenomegaly

Discussion

These results support the contention that the prognosis in ALL

in adults is influenced by the extent of disease at presentation.

The presence of hepatosplenomegaly was associated with a very short

duration of remission. All patients with a very high blast count

(greater than 100x 10 high 9/1) had relapsed within six months.

even though the previously significant adverse influence of a presentation

blast count above lOx 10 high 9/1 has not been confirmed. The cell

surface marker studies demonstrate a significant advantage for patients

whose blast cells reacted with the anti-ALL serum. The number of

patients was small and the findings should be interpreted with caution.

However. the fact that the results are identical with those reported

in childhood ALL reported by Chessels et al. Chessels and Hardisty

(1977) suggests that our observations are valid. The response to

the initial therapy remains the most important prognostic factor.

with survival being very significantly longer for patients in whom

complete remission was achieved than for those in whom it is not.

The recognition that the same prognostic factors apply to both childhood

and adult lymphoblastic leukemia makes it possible to develop treatment

programmes for adults on the basis of data obtained from childhood

studies. This is most important since the number of adults with

lymphoblastic leukemia is small and data are hard to obtain. The

recognition that presentation features influence the prognosis must

lead to the intensification of therapy for patients with adverse

prognostic factors and also the avoidance of intensification of

therapy for those patients in whom adverse prognostic factors are

not found.

References

I. Armitage. P.: Statistical Methods in Medical Research. London:

Halstead Press 1971

2. Atkinson. K.. Wells. D.G.. Clinik. H.. Kay. H. E. M.. Powles.

R.. Mc Elwain. T..J.: Adult acute leukemia. Br. .J. Cancer30, 272-278

(1974)

3. Bennett. .J. M.. Catovsky. D.. Daniel. M.- T.. Flandrin. G..

Gralnick. H. R.. Sulton. C.: Pro posals for the classiflcation of

acute leukemias. Br. .J. Haematol. 33,451-458 (1976)

4. Brown. G.. Capellaro. D.. Greaves. M. F.: Leukemia-asso(iated

antigens in man. .J. Natl. Can(er Inst. 55, 1281-1289 ( 1975)

5. Chessells. .J. M.. Hardisty. R. M.. Rapson. N. T.. Greaves. M.

F.: Acute lymphoblasti( Ieu kemia in children: Classification and

prognosis. Lancet 1977II, 1307-1309

6. Einhorn. L.H.. Meyer. S.. Bond. W.H.. Rohn. R..J.: Results of

therapy in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Oncology 32,214-220

( 1975 )

7. Gee. T. S.. Haghbin. M.. Dowling. M. D.. Cunningham. I.. Middleman.

M. P.. Clarkson. B.: A(ute Iymphoblastic leukemia in adults and

children. Cancer37, 1256-1264 (1976)

8. Henderson. E. S.: Treatment of acute leukemia. Semin. Hematol.

6,271-319 (1969)

9. .Jacquillat. C.. Weil. M.. Gemon. M. F.. Auclerc. G.. Loisel.

.J. P.. Delobel. .J.. Flandrin. G.. Schaison. G.. Izrael. Y.. Busel.

A.. Dresch. C.. Weisgerber. C.. Rain. D.. Tanzer. .J.. Najean. Y..

Seligmann. M.. Boiron. M.. Bernard. .J.: Combination therapy in

130 patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Protocol 06 LA 66-Paris).

Cancer Res. 33, 3278-3284 (1973)

10. Lister. T. A.. Whitehouse. .J. M. A.. Beard. M. E..J.. Brearlev.

R. L.. Brown. L.. Wriglev. v c P. F. M.. Crowther. D.: Earlv central

nervous svstem involvement in adults with acute non myelogenous

leukemia. Br...J. Cancer 35,479--483 ( 1977)

11. Lister. T.A.. Whitehouse. .J.M.A.. Beard. M.E..J.. Brearlev.

R.L.. Wriglev. P.F..M.. Oliver. R.T. D.. Freeman. .J. E.. Woodruff.

R. K.. Malpas. .J. S.. Paxton. A. M..vCroowther. D.: Combination

chemotherapy f(or acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Br. Med.

.J. 1, 199-203 (1978)

12.Muriel. F.S.. Pavlovsky.S.. Penalver. .J.M.. Hidalgo.G.. Benesan.

A.C.. EppingerHelft. D., De Macchi, G. H., Pavlovsky. A.: Evaluation

of induction of remission. intensification and central nervous system

prophylactic treatment in acute Iymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 34,418-426

( 1974 )

13. Peto, R., Pike. M. C., Armitage. P.. Breslow. N. E., Cox, D.

R.. Howard, S.Y.. Mantel. S. Y., Mc Pherson. K., Peto. .J., Smith,

P.G.: Design and analysis of randomised clinical trials requiring

prolonged observation of ea(h patient. II. Analysis and examples.

Br. .J. Cancer 35, 1-39 (1977)

14. Roberts, M. M., Greaves, M. F.. .Janossy, G., Sutherland, R..

Pain. C.: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) Associated Antigen

-I. Expression in Different Haemotopoietic Malignancies, Leukemia

Resear(h. 2 ( no.1) 105-114 ( 1978 )

15. Rodriguez, Y.. Hart, .J. S.. Freireich. E. .J., Bodev. GJ. P.,

M(Credie, K. B., Whitecar. .J. P.. Coltman. C. A.: POMP combination

Chemotherapy of adult acute leukemia. Cancer 32, 69-75 (1973)

16. Simone, .J.Y.. Yerzosa, M.S., Rudy, .J.A.: Initial features

and prognosis in 363 children with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer36,

2099-2108 (1975)

17. Spiers. A. S. D.. Roberts, P. D., Marsh. G. W.. Paretch. S.

.J.. Franklin, A..J.. Galton. D. A. G.. Szur. Z. L.. Paul, E. A..

Husband, P.. Wiltshaw, E.: Acute Iymphoblasti( leukemia: Cy(lical

chemotherapy with 3 combinations of 4 drugs (COAP-POMP-(ART regimen).

Br. Med. .J. 4,614-617 (1975)

18. Whitecar, .J. P.. Bodey. G. P., Freirei(h, E..J.. McCredie,

K. B.. Hart, .J. S.: Cyclophosphamide (NSC -26271 ). Vincristine

(NSC-67574 ), Cvtosine Arabinoside (NSC-63878). and Predisone (NSC-10023)

(COAP) combination Chemotherapy for acute leukemia in adults. Cancer

Chemother. Rep. 56,543-550 ( 1972)

19. Willemze, R.. Hillen. H.. Hartgrink-Groeneveld, C.A.. Haanen.

C.: Treatment of acute Iymphoblasti( leukemia in adolescents and

adults: A retrospective study of 41 patients ( 1970-1973). Blood

46,823-834 ( 1975)

|