|

Institute of Cancer Research and Department of Human

Genetics and Development, College of Physicians and Surgeons, RNA Tumor Viruses and Human Leukemias Considerable information

is available concerning the etiological role of RNA tumor viruses

in leukemias, lymphomas, sarcomas, and breast cancer in a variety

of animals, e.g., chicken (1), mice (2), cats (3), etc. In animals,

causative proof has been achieved by inoculation experiments that

satisfy Koch\'s postulates. In man, such experiments obviously cannot

be undertaken, and other more indirect evidence has to be assembled

to clarify the etiology of human malignancies with its implications

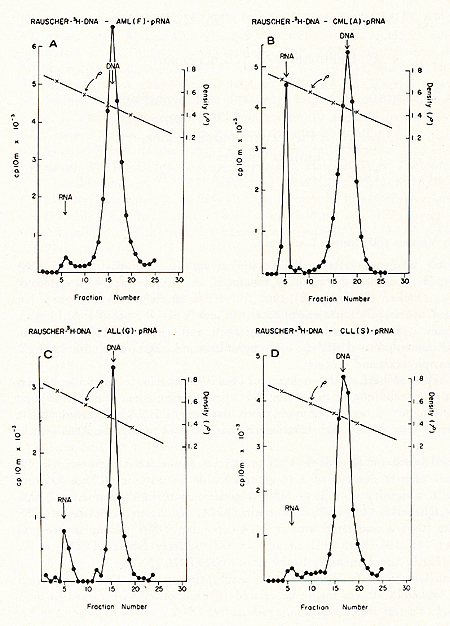

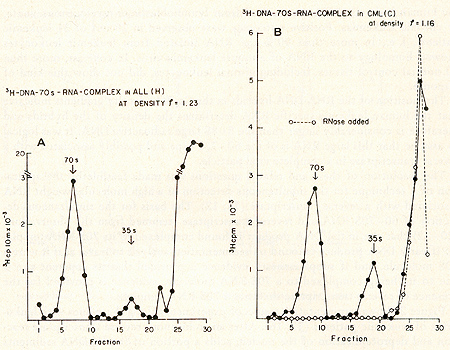

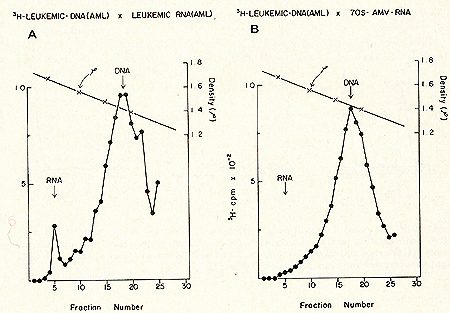

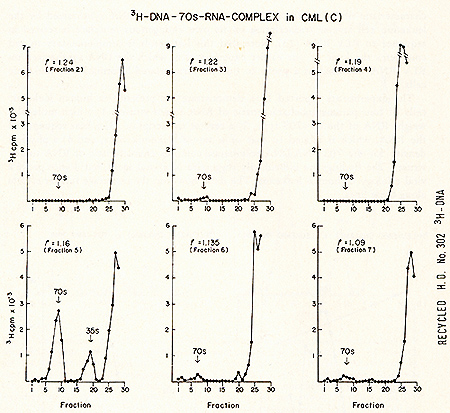

for prophylaxis and therapy.  Fig. 1: Cs2S04 density profiles of hybridization reactions between ³H-RLV-DNA and cytoplasmic RNA isolated from human leukemic white blood cells. ³ H-RL V -DNA and cytoplasmic RNA were prepared as described (7). About 350 µg RNA was hybridized to 2000 cpm of purified, heat denatured ³H-RLV-DNA (10,000 cpm/pmol) for 18 hr at 37 °c in the presence of 0.4 M NaCI and 50% formamide (total vol 60 µl). After incubation, the reaction mixture was added to 10 ml half-saturated Cs2S04 (p = 1.52 g/cm³) in 5 mM EDTA and centrifuged at 44,000 rpm in a 50 Ti rotor (Spinco) for 60 hr at 15 °C. Fractions of 0.4 ml were collected from below and assayed for TCA-precipitable activity. The cytoplasmic RNA was derived from A) AML (F), B) CML (A), C) ALL (G), D) CLL (S). Positive outcomes were observed in 28 out of 31 leukemic patients, i. e., in more than 90% the RNA isolated from leukemic leukocytes showed homology to the RNA of a mouse leukemia virus. In contrast, more than 50 normal control tissues, including normal leukocytes, did not show this kind of response. The position of the RNA-DNA-hybrids in the CS2 SO4 density gradients indicates that the human leukemia-specific RNA determines the density of the hybrids and therefore is considerably larger than the 5-8S large radioactive DNA. It was logical to assume that this large RNA is of the 60- 70S type and possibly associated with a reverse transcriptase in a complete viral particle. The resolution of these and related questions was made feasible by the apllication of a technique for the simultaneous detection of a high molecular weight RNA associated with a reverse transcriptase (11, 12). The basis for the simultaneous detection of 60- 70S RNA and reverse transcriptase stemmed from the observations (20-22) that the initial DNA product is found complexed to its 70S-RNA template. If early DNA product is found on sedimentation analysis to travel as if it were a 70S molecule, and if supplementary evidence is provided that its apparent size is due to its being complexed to a 70S-RNA molecule, evidence is provided for the presence of reverse transcriptase that uses a 70S-RNA template. Figure 2 shows representative results of experiments along these lines with leukocytes of leukemic patients (13,16). After an endogenous reverse transcriptase reaction and deproteinization of the nucleic acids a portion of the ³H-DNA sediments in discrete 70S and 35S peaks in glycerol-sedimentation-gradients. After RN ase digestion, the entire radioactive DNA is found in the low molecular weigh t region of the gradient, as exemplified in Fig. 2B. This proves that the ³H-DNA was complexed to a high molecular weight RNA. In Fig. 2, experiments with cell material from patients with ALL (A) and CML (B) are shown. In total, more than 50 leukemic cell samples gave the specific DNA-synthesis resulting in ³H-DNA com plexed to a 70S RNA whereas only one out of 27 normal white blood cell samples yielded evidence for this type of activity. In this case, the available white blood cells did not permit further characterization by hybridization and thus an unambig uous statement as to the nature of this positive reaction cannot be made. After extensive alkali digestion to destroy all RNA present, the ³H-DNA was recovered and annealed to viral-enriched RNA of the same leukemic cells that had been used for the specific DNA synthesis. From Fig. 3A, it is clear that about 20 % of the ³H-DNA is shifted from the DNA region to the hybrid and RNA regions of the gradient due to formation of RNA-DNA hybrid structures. when the same human ³H-DNA is annealed with an equivalent amount of AMV-70S-RNA, no evidence of hybrid formation is seen (3B). This back hybridization completes the operational definition of a reverse transcriptase and shows that human leukemias contain 70S RNA-associated reverse transcriptase. These data are in agreement with the finding by other groups of reverse transcriptase in human leukemic cells (23, 24 ).  By density fractionation of the leukemic cytoplasm, it could be shown that this 70S-RNA-DNA polymerase complex has a density of 1.16 g/cm³ (Fig. 4 ), which is characteristic of RNA tumor viruses (16). Further, the DNA synthesized by the leukemic cell reverse transcriptase on its own endogenous template is related in sequence to RLV RNA (13). Note that this last result is complementary to and completes the logic of our earlier experiments in which the DNA synthesized on RL V RNA was used as a probe to find the virus-related information in leukemic cells. The experiments reported here demonstrate the presence in human leukemic cells of four parameters characteristic of RNA tumor viruses: 1) a high molecular weight RNA of the 60- 70S type, 2) a reverse transcriptase, 3) a base sequence of the RNA, which is related to that of a mouse leukemia virus, and 4) a physical density for the 70S RNA-DNA-polymerase complex characteristic of RNA tumor viruses. The findings are individually suggestive of a viral agent, but do not prove a viral etiology of human leukemia. The data, however, do encourage further efforts along these lines.  Fig. 3: CS2 SO4

equilibrium density gradient centrifugation of annealing reactions

of human leukemic (AML [TI) ³H-DNA to (A) 85 µg human leukemic (AML

[TI) RNA enriched in viral sequences by prior density fractionation

of cytoplasmic material and subsequent RNA extraction from the 1.10-1.26

g/cm³ density region, and (B) 0.5 µg highly purified 70S AMV -RNA.

A standard RNA-instructed DNA polymerase reaction was performed

as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The high molecular weight

RNA ³H-DNA complex obtained after glycerol sedimentation centrifugation

was digested with 0.4 M NaOH for 18 hr at 37 °c to remove all RNA

present. The ³H-DNA product was then annealed to the respective

RNAs in a vol of 60 µI in the presence of 50% formamide and 0.4

M NaCl. After annealing for 18 hr at 37 °C, the reaction mixture

was subjected to CS2S04 gradient centrifugation as described under

Fig. 1.  Fig.4: Sedimentation profiles of a complete set of simultaneous detection

tests after sucrose density fractionation of leukemic cytoplasm.

2 9 of white blood cells from a patient with CML (Con) were prepared

and examined as described in Fig. 2. Acknowledgments The excellent technical assistance of Jeanne Myers and Lee Hindin

is appreciated. References |