|

1 Johns Hopkins Oncology Center, 600 North Wolfe

Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA

A. Introduction

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in the treatment of acute

leukemia has shown remarkable therapeutic progress in recent years.

Long-term remissions and possible cure rates of 50% or higher have

been obtained by a number of centers in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia

(ANL), particularily when patients were transplanted in their first

remission [ 1-9]. Most reported series of allogeneic marrow transplantation

in acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) performed in the second remission

have shown long-term disease-free survival of 20%30%. Data for patients

in their third and subsequent remissions are less good [10-14].

The recent report from the Memorial Sloan Kettering group [15] and

the Baltimore group [16] has shown a therapeutic improvement over

the previously reported series of ALL transplanted in their second

remission. In the present communication, we wish to update our results

of allogeneic marrow transplantation in patients with ANL and ALL

who received marrow grafts from genotypically HLA-identical siblings.

B. Material and Methods

I. Informed

Consent All protocols were reviewed and approved by The Johns Hopkins

University Institutional Review Board.

II. Patient Selection

To be eligible for these studies, patients had to have a diagnosis

of ANL or ALL confirmed by examination of a marrow aspirate. In

addition, for ANL, they had to have a negative history for central

nervous system leukemia and, for both ANL and ALL, a spinal fluid

free of leukemic cells on cytocentrifuge examination at admission.

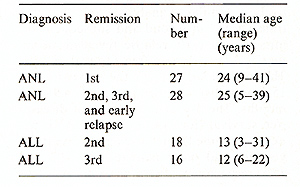

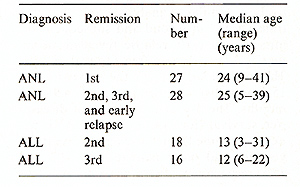

All data were analyzed as of 15 April 1984. A total of 27 patients

with ANL were transplanted in their first remission and 28 patients

in their subsequent remissions and early relapse; 18 patients with

ALL were transplanted to the second remission and 16 in their third

remission. The characteristics of each patient group are noted in

Table 1.

III. Marrow Grafts

Marrow aspiration was performed under general anesthesia. The technical

aspects of the marrow collection and administration were as described

previously [ 17].

Table I. Characteristics of patients with

ANL and ALL

IV. Preparation for Engraftment

Patients with ANL were prepared with oral busulfan (BU) given in

divided doses over a 4-da y period for a total dose of 16 mg/kg.

This was followed by cyclophosphamide (cY) given intravenously (i.v.)

at a dose of 50 mg/kg for four consecutive daily doses. Patients

with ALL were prepared with cy given i.v. at a dose of 50 mg/kg

for four consecutive daily doses followed by low dose rate total

body irradiation (TBI) of 300 rad/day for four consecutive daily

doses (lungs shielded for the third dose ). All patients received

one intrathecal injection of methotrexate (10 mg/m², but not more

than a total of 12 mg) before cytoreductive therapy.

V. Treatment After Marrow Grafting

Patients were given cy or cyclosporine prophylactically to prevent

graft-versushost disease. Prophylaxis for central nervous system

leukemia was given 50-80 days after marrow transplantation as five

intrathecal doses of methotrexate (10 mg/ m²) over 10-14 days.

C. Results

Analysis by Kaplan-Meier plots for patients with ANL revealed

an actuarial 3-year disease-free survival and median duration of

living survivors (range) for patients transplanted in the first

remission of 44% and 33.4 months (2.4-61.3 months) respectively.

Similar analysis of patients transplanted in second and subsequent

remission and early relapse revealed an actuarial 3-year disease-free

survival of 43%. The median survival for the survivors was 15.7

months with a range of 4.9-46.5 months. The 3-year probability of

diseasefree survival (for both groups of ANL patients combined)

for those aged 20 years or younger and older patients was 61% and

35%, respectively. There was only one leukemic relapse in this entire

series. This occurred I year after transplantation in a 36year-old

male transplanted in his third remission. Of 18 patients with ALL

transplanted in their second remission, 9 survive in continuous

remission from 1.2 to 49 months (median 19.2 months). The probability

of a 2-year disease-free survival is 48%. There have been no relapses

in this group. Of 16 patients (6 in continuous remission) with ALL

transplanted in their third remission, 8 survive for 2.3-46.8 months

(median 22.3 months) with a projected 2-year survival of 46%. Six

relapses were seen. The projected 2-year probability of remission

was 44%. The causes of deaths in both the ANL and ALL series of

patients were similar. Some 80% of the deaths were related to graft-versus-host

disease and viral infections.

D. Discussion

Our initial series of patients transplanted for ANL following preparative

treatment with BU and cy have been previously reported [8]. The

present extension of that study with additional time and more patient

entry continues to show promise. In particular, the very uncommon

relapses ( I of 55 patients) suggests that this regimen may well

have a more profound antileukemic effect than other reported treatments.

Other possible practical or future advantages for this preparative

treatment have been noted previously. The studies in ALL are not

quite so advanced, but already it appears that the transplantation

of patients with ALL following the CY- TBI protocol outlined here

results in a therapeutic response better than most reported series

and at the moment is at least similar to the Memorial-Sloan Kettering

experience using hyperfractionated TBI followed by cy [ 15]. Because

of the high relapse rate of ALL patients in the third remission,

we are currently preparing patients for transplantation with BU

and cy as outlined for ANL. Graft-versus-host disease and viral

infections continue to be a major cause of death. A number of laboratories

in transplant centers are intensively investigating approaches to

the prevention and treatment of these complications. Some of these

studies already show considerable promise. It is reasonable to assume

therefore, that within the next few years disease-free survivals

following allogeneic marrow transplantation may increase by 20%-30%.

Acknowledgements. This work was supported by PHS Grants CA-15396

and CAO-6973 awarded by The National Cancer Institute, DHHS.

References

I. Thomas ED, Buckner CD, Clift RA et al. (1979) Marrow transplantation

for acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia in first remission. N Engl J

Med 301:597-599

2. Forman SJ, Spruce WE, Farbstein MJ et al. (1983) Bone marrow

ablation followed by allogeneic marrow grafting during first complete

remission of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Blood 61: 439-442

3. Powles RL, Morgenstern G, Clink HM et al. (1980) The place of

bone-marrow transplantation in acute myelogenous leukaemia. Lancet

I: 1047-1050

4. Kersey JH, Ramsey NKC, Kim T et al. (1982) Allogeneic bone-marrow

transplantation in acute non-lymphocytic leukemia: A pilot study.

Blood 60:400-403

5. Zwaan FE, Hermans J, for the E.B.M.T. Leukaemia Working Party

(1982) Bone-marrow transplantation for leukaemia. European results

in 264 cases. Exp Hematol 10 (suppl 10):64-69

6. Mannon P, Vemant JP, Roden M et al. (1980) Marrow transplantation

for acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia in first remission. Blut 41:

220-225

7. Gale RP, Kay HEM, Rimm AA et al. (1982) Bone-marrow transplantation

for acute leukaemia in first remission. Lancet 2: 1006 -1009

8. Santos GW, Tutschka PJ, Brookmeyer R et al. (1983) Marrow transplantation

for acute non-lymphocytic leukemia following treatment with busulfan

and cyclophosphamide. N Engl J Med 309: 1347-1353

9. Dinsmore R, Kirkpatrick D, Flumenberg N, Gulati S, Kapoor N,

Brochstein J, Shank B, Reid A, Groshen S, O'Reilly R (1984) Allogeneic

bone-marrow transplantation for patients with acute non-lymphocytic

leukemia. Blood 63:649-656

10. Thomas ED, Sanders JE, Floumoy Net al. (1979) Marrow transplantation

for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in remission. Blood

54:468-476

II. Johnson FL, Thomas ED, Clark BS, Chard RL, Hartmann J R, Storb

R ( 1981) A com parison of marrow transplantation to chemotherapy

for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in second or subsequent

remission. N Engl J Med 305: 846-851

12. Scott EP, Forman SJ, Spruce WE et al. (1983) Bone-marrow ablation

followed by allogeneic bone-marrow transplantation for patients

with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia during complete remission.

Transplant Proc 15:1395-1396

13. Kendra JR, Joshi R, Desai Met al. (1983) Bone-marrow transplantation

for acute lymphoblastic leukemia with matched allogeneic donors.

Exp Hematol II (suppl 13): 9 (abstract)

14. Woods WG, Nesbitt NE, Ramsey NKC et al. (1983) Intensive therapy

followed by bonemarrow transplantation tor patients with acute lymphocytic

leukemia in second or subsequent remission: Determination of prognostic

factors (A report from the University of Minnesota Bone Marrow Transplantation

Team). Blood 61: 1182- 1189

15. Dinsmore R, Kirkpatrick D, Flomenberg N et al. ( 1983) Allogeneic

bone-marrow transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Blood 62: 381-388

16. Santos GW (1983) Allogeneic and syngeneic marrow transplantation

for acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) in remission. Blood 62:229

17. Thomas E, Storb R (1970) Technique for human marrow grafting.

Blood 36:507-515

|